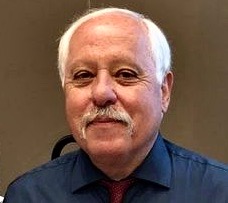

To mark the 40th anniversary of my summer as a

tour guide and boat operator at Crater Lake National Park (below, right), friend Frank Czubiak and I hit the

road for a few days of fun and adventure in and around "the jewel of the Cascades" on Monday, July 29.

To the indigenous inhabitants of the marshes south and east of the mountain they called Lao-Yaina (Llao’s mountain), Crater Lake was a powerful, mystical place, home of the evil deity, Llao, who resided inside Mt. Mazama. Along with his minions, a collection of lesser spirits who could change their worldly forms at will, Llao was the supreme ruler of the underworld, of earthquakes, smoke and fire.

The Klamath and Modoc tribes, who settled in the basins

near Mt. Mazama about 13.000 years ago as the Pleistocene meltout filled the

giant lakes and marshes, were understandably fearful of the mountain, at that

time one of the great volcanoes of the world. The massif was revered and full of

symbolism, and tribal shamen would weave tales of mystery

and imagination about the dwelling of Llao.

While the prince of darkness occupied the grim mass north of

the marshes, Skell -- the benign god of the earth and sky -- ruled to the south

on the lofty, white dome known today as Mt. Shasta. Rejected and humiliated by the daughter of

a Klamath chieftain, the lovelorn Llao sought revenge, trying to destroy her

people with a curse of fire, and battled with Skell, her protector.

The evil deity thundered and spewed rivers of fire, burning rocks and lethal black gas on the

villages below. A fierce war raged between these gods until

Skell vanquished the lord of the underworld, forcing the summit of Mt. Mazama

to collapse and sending the subjects of Llao into the seething remains of the

mountain.

Seeking peace and tranquility, Skell filled the dark pit with blue water. But fearing its mysterious powers and evil past, Native

Americans tended to leave Crater Lake alone. Shamen warned that death would

come to anyone who gazed upon the indigo blue waters.

John Wesley Hillman, the first white man to “discover”

Crater Lake, was puzzled by the indifference shown by the Native Americans to

his discovery: “Stranger to me than our discovery was the fact that I could get

no acknowledgement that any such lake existed; each and every one denied any

knowledge of it,” he wrote in his journal.

White settlers in the

vicinity and subsequent generations of immigrants would not be immune from the evil spirits lurking in the deep blue

waters of Crater Lake. But those are tales for another day. On this day, we had

been bedeviled by “Curse of Llao.”