This year marks two significant milestones: the

establishment of The Wilderness Act of 1964 and my first job as a backcountry

ranger on the Malheur National Forest in 1974. To celebrate the first legal

definition and status for true wilderness, a group of us -- all former Forest Service employees on the Wenatchee River Ranger District -- will convene in the Glacier Peak Wilderness on August 17.

The legal protection of wilderness in America is nothing

short of one of the most significant events in our brief history, and the list of names

of people who contributed to what has become known as “The Act” is significant:

Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Theodore Roosevelt, John Muir,

Gifford Pinchot, Aldo Leopold, Bob Marshall and Howard Zahniser, just to name a few.

Today,

we might consider the idea of national parks and forests -- and even true

wilderness -- as a given. Why then, did it take nearly 200 years after the

establishment of this country to finally protect wilderness from development -- something that would be so essential to the public good, and for so many

reasons? The short answer is because of competing interests.

We must remember that “wilderness” was once something to be

conquered and overcome for the sake of civilizing this infant country. And with

seemingly unlimited natural resources available at hand, greed and avarice in

the name of capitalism and “progress” certainly slowed the development of the movement

to preserve federal lands for the good of future generations.

The

seeds of wilderness preservation were planted in the mid-19th

century writings of Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson and John Muir. “I went

to the woods because I wished to live deliberately,” wrote Thoreau, “to front

only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to

teach.”

Muir, whose letters, essays and books describing his

adventures in nature, and particularly in the Sierra Nevada mountains of

California, were read by millions of Americans, was an early advocate for the

preservation of wilderness in the U.S. “The clearest way into the Universe is

through a forest wilderness,” he wrote.

As

early as the 1880s, Benjamin Harrison, a Senator and future President of

the U.S., introduced legislation to preserve the Grand Canyon as a “public

park.” Unfortunately, the bills all perished in committee. Beyond the politics

of the day, however, this was a struggle between personal profit and the public

good. It would turn out to be a long and difficult trek to the Wilderness Act

of 1964.

Ultimately, Theodore Roosevelt, the 26th

President of the United States, would become the champion for wild land protection -- along with his key advisors, the twin lightning rods for preservation and

conservation, respectively -- Muir and Gifford Pinchot. Roosevelt had an

affinity for the natural environment that, especially when compared to his

predecessors, was unprecedented.

Roosevelt

also had the exuberant personality to make things happen. In 1887, he

founded the Boone and Crockett Club, a conservation organization

named for hunter-heroes Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett. The

group was responsible for the elimination of commercial market hunting, the

creation of national parks, forests and wildlife preserves, and funding

mechanisms for conservation.As president, Roosevelt would take it up a notch or two during the “preservationist revolution of 1908.” In “The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and The Crusade for America,” author Douglas Brinkley notes that Roosevelt, an avid birder and outdoorsman, “had (already) far exceeded any other individual in U.S. history in his efforts to preserve the natural wonders of the West.”

But Roosevelt was also aware that his objectives were still hindered by slow-moving legislators in the U.S. Congress, noted Brinkley. Conservation was, above all else, a moral issue to Roosevelt. (He) "needed a better weapon against congressional lethargy in matters of conservation, and he found it in federal bird reservations, big game commons and national monuments (as set forth by the Antiquities Act of 1906).”

By 1908, Roosevelt’s characteristic impatience made it increasingly difficult for him to abide by the old rules and wait for legislators to see the light. Most politicians of the day made backroom deals, but the supremely self-confident Roosevelt did most of his political maneuvering in full view of the public, and he always welcomed scrutiny. He would just declare something and let the chips fall wherever they may.

If Congress was asleep, Roosevelt was going to wake it up; his job as president was to procure the most happiness for the most

people, and the Grand Canyon would become a flashpoint for action. He believed the Grand Canyon should be a truth for all time, not to be denied to future

generations -- a holy spot. Two days after signing the Muir Woods initiative,

he declared the Grand Canyon a national monument.

He

made it clear that no parcel of wilderness -- public, private or other -- would

be immune from potential seizure by the federal government. Roosevelt’s

preservationist initiatives were as simple as they were decisive. With no

worries about re-election in 1908, he stood ready to engage the “American

goliath,” which he later defined as a “vicious plutocracy” with the morals of

“glorified pawnbrokers.”Roosevelt was well suited to conflict and acrimony. By 1908, he had made an impressive number of enemies, including John D. Rockefeller and J.P. Morgan, among others. Yet, Roosevelt had “no more potent ally than the press” in his corner, noted Rockefeller’s biographer Ron Chernow. After all, clashes between Roosevelt and the corporate titans of America made good copy.

Yet, though the icons of the Gilded Age spent millions of dollars on advertising in an attempt to smear Roosevelt’s reputation and cripple him politically while exhausting him personally, they had failed on every count. Each swipe had the opposite effect, bolstering his obstinacy. Indeed, he had licked them at their own game.

On May 13, 1908, he initiated his “coup de grace” for the

preservationist movement at the Conference of Governors at the White House. The

president had asked for each governor to bring three competent advisors on

natural resource management. The nine justices of the U.S. Supreme Court were

also in attendance, something unprecedented for a blue ribbon commission.

In

his opening remarks, Roosevelt noted: “We have become great in a material sense

because of the lavish use of our resources, and we have just reason to be proud

of our growth. But the time has come to inquire seriously what will happen when

our forests are gone, when the soils shall have been further impoverished and

washed into the streams, polluting the rivers.”“One distinguishing characteristic of really civilized men is foresight,” he continued. “We have to exercise foresight for this nation in the future.”

Some in attendance criticized his intentions to advance the cause of preservation, but most of the presentations at the conference came from those who were terrified by the prospect of America’s vanishing natural resources.

Encouraged by the response, Roosevelt’s resolve to create new forest and game reserves and enlarge old ones had been bolstered. But he would leave nothing to chance. In June, the president prepared a massive preservationist initiative that was stunning in both its scale and breadth of vision. Roosevelt clearly subscribed to the philosophy of Edmund Burke, who wrote about “the wisdom of ancestors.”

On July 1, 1908, the last full year of his presidency, Roosevelt created 45 new national forests scattered throughout 11 western states.

All told, a total of 93 federal forest sites were created within a 24-hour period, with innovative protocols for range management, wildfire control, land use planning, recreation, hydrology and soil science introduced throughout the American West.

Yet, despite significant gains in the preservation movement during Theodore Roosevelt's administration, the concept of “wilderness for the sake of wilderness” remained elusive. “It was not until the New Deal years of the 1930s that recreational use of national forests, always of some interest, began to receive truly serious consideration,” wrote Harold K. Steen in “The U.S. Forest Service: A History.”

Steen noted that up until 1935, the U.S. Forest Service gave no formal recognition to recreation. “Annual reports lumped it in with game. From the Forest Service point of view, two recreational elements -- wilderness and national parks -- presented the most difficulty.”

Soon, however, two individuals would take the concept of wilderness to the next level: Aldo Leopold and Bob Marshall.

Leopold, author of the seminal naturalist tome, A Sand

County Almanac, was a scientist, ecologist, forester and environmentalist and a

key figure in the movement for wilderness conservation. A U.S. Forest Service

employee early in his career, Leopold would become a professor of forestry at

the University of Wisconsin. By the 1930s, Leopold was the nation’s foremost

expert on wildlife management.

In Leopold’s mind, the concept of “wilderness” also took

on a new meaning; he no longer saw it as a hunting or recreational ground, but

as an arena for a healthy biotic community. “To

those devoid of imagination,” he wrote, “a blank place on the map is a useless

waste; to others, the most valuable part. There are some who can live without

wild things, and some who cannot.”

Bob Marshall, a forester and wilderness activist, is

another key player in the wilderness preservation movement. As an

employee of the Forest Service, he recommended a survey so that decision

makers might know the preferred types of recreation and how much land ought to

be dedicated for these purposes. His approach provided a unified approach to

recreation, adding a sense of permanency.

Both

Leopold and Marshall were founders of The Wilderness Society in 1935. “I

believe we have a profound fundamental need for areas of the earth where we

stand without our mechanisms that make us immediate masters over our

environment,” said Marshall. Nearly 30 years later, The Wilderness Society

would be instrumental in passing The Wilderness Act, which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year.

The Wilderness Act, which required over 60 drafts and eight

years of work, is known for its succinct definition of wilderness: “A

wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate

the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its

community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who

does not remain.”

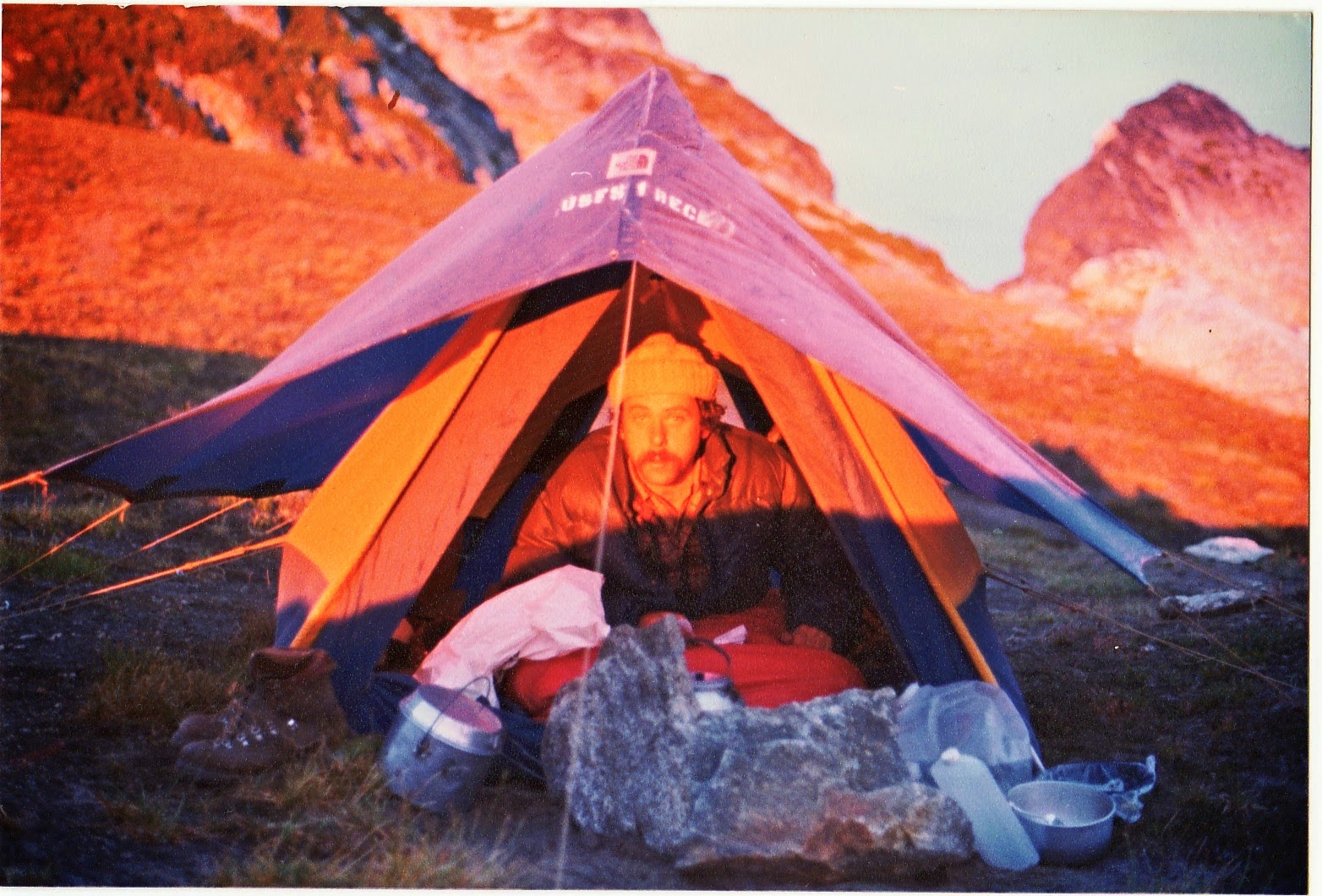

Ten years after the establishment of the Wilderness Act, I

was hired as a backcountry ranger at the Prairie City Ranger District on the

Malheur National Forest, where I patrolled the Strawberry

Mountain Wilderness. Hired by the Wenatchee National Forest in 1975, I worked

on the trail crew initially, and later roamed the Glacier Peak Wilderness

and Alpine Lakes Wilderness as a backcountry ranger.

In a few short weeks, my former U.S. Forest Service

compatriots and I will gather for a reunion -- a backcountry hootenanny for the

ages -- in Spider Meadows in the Glacier Peak Wilderness in the upper Chiwawa

River area of the Wenatchee River Ranger District. To paraphrase John Muir, the

mountains are calling, and we must go.