Growing up in Portland, I experienced “the freedom of the hills” at a young age: first, through my involvement in our

parish Boy Scout troop, and then with my Dad (below, taking a break before the summit push), who led climbs locally for

students at John Marshall High School, where he taught physics, chemistry and

general science.

In those days, my mountain role models included a number of legendary

climbers from the Northwest: Jim Whittaker, the first American to reach the

summit of Mt. Everest, his twin brother Lou Whittaker, Willi Unsoeld and Fred Beckey, who has made hundreds of first ascents, more than any other North

American climber.

And they were considerable: first solo ascent of Mt. Everest

without supplemental oxygen, the first climber to ascend all 14

“eight-thousanders” (peaks over 8,000 meters, or 26,000 feet, above sea level),

and the fastest-to-that-point ascent of the north face of The Eiger (below, left, with Monck on the right) in the

Swiss Alps.

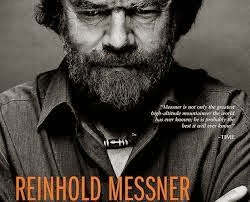

Having just finished Reinhold Messner: My Life at the Limit, written by Thomas Heutlin in interview style punctuated with narrative, what struck me is how closely Messner’s philosophy of wilderness,

adventure and climbing aligns with my own views and that of many of my mates

from The Aldo Leopold Society (below).

On feelings of immortality: “Yes, there was a kind of naïve

‘it won’t get us’ feeling. It wasn’t that we were better than the others, but

we’d just been through hell together; it couldn’t get any worse than that. You

operate in a world where humans do not belong, a place where it seems totally

irrational to go.”

“Failure itself is not important. It’s what happens after that counts, the inner feelings, the turmoil and self-doubt, and how you deal with it. It can mean a new start, an opportunity to

experience your limitations and to grow as a result. My attitudes have changed

over the years, and this is largely due to my frequent failures.”

“Gottfried Benn put it well when he said that mountaineering

is about challenging death and then resisting it. Death has to be a

possibility. The art of mountaineering lies in resisting it, in surviving. The

symptom of my disorder is defined as a lust for life that comes from putting my

life at risk.”

On his biggest regret: “The death of my brother on

Nanga Parbat. I came to the conclusion that life is limited and only

worth something if you exploit its full potential, if you savor it to the

fullest. After that tragedy, which nearly killed me, I lived life much more

intensely. It challenged me to keep living with double the effort.”

On his museum projects: (It’s) “primarily concerned with

what happens inside of a person when they encounter the mountains. When you

climb a mountain, you come back down a different person. We don’t change the

mountain by climbing it; we ourselves change. But plenty happens to the person.

Up there all the masks fall.”