Less than 24 hours after seeing Pat Metheny at The Shedd,

Rebecca and I had third row seats for “An Afternoon With Bill Cosby” at the Hult Center for Performing Arts in downtown Eugene, compliments of daughter Gina as a 35th wedding anniversary present.

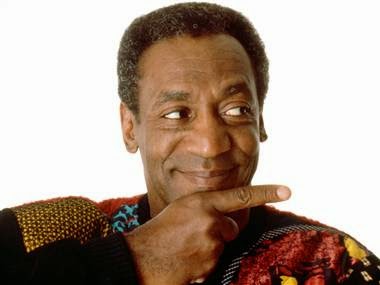

After making the rounds last year, the “Cos” was on the circuit once again with his “Far From Finished” tour. Some will remember Bill Cosby from what was arguably television’s biggest hit of the 80s (below), a show that singlehandedly rejuvenated the sitcom genre and revived the ratings fortunes of NBC.

My connection with Cosby, however, dates back to the mid-60s when comedy albums were the rage. Many standup comics of day found they could reach a much broader audience by recording their bits on “record albums.” Yes, kids, we’re talking about vinyl here.

This golden era of comedy featured humorists like Shelly

Berman, Lenny Bruce, Woody Allen, Mel Brooks and Carl Reiner, Elaine May and

Mike Nichols, George Carlin, Dick Gregory, and Bob Newhart, who had

back-to-back No. 1 comedy albums in the early 60s.

The king, however, was a standup comic from Philadelphia

named Bill Cosby, who won five consecutive Grammys in the 60s. Spin Magazine lists

Cosby’s “To My Brother Russell, Whom I Slept With” as No. 1 on its Top 40

Comedy Albums of All Time. Spin notes that the recording is “standup comedy’s

masterpiece.”

About 300 contestants competed in humorous and serious categories featuring three types of verbal discourse: oratory, a

memorized speech practiced months before the competition; extemporaneous,

a speech (also practiced) read with enthusiasm using tone and inflection from a script;

and impromptu, a speech that each participant created on the spot based on random

subjects issued by judges.

In 1966, I won first place in the serious category with a

speech using the closing argument of defense attorney Atticus Finch in “To Kill

A Mockingbird” by Harper Lee. The next year, I tried my hand in the humorous

category and won using the two excellent Cosby bits, despite receiving an

inordinately low score by one of the three judges.

Two

of three judges placed me first, while the third had me coming in fourth place.

I suspected racism, though I would never be able to prove it. But the potential

for racial bias was certainly not out of the realm of possibility in those days. After all, I

had used the comedy material of an African-American, and racism was still very

prevalent in this country. Remember, this was the 60s.

That same year, Cosby became the first black actor in a lead

role in an American dramatic television series: “I Spy” featured Robert Culp as Kelly

Robinson and Bill Cosby as Alexander Scott (above), a pair of federal intelligence

agents posing as a tennis pro (Culp) and his coach and comedic foil (Cosby).

These "feds" faced their adventures in espionage with skill, humor and some serious questions about their work. Robinson’s cover was as a former Princeton law student and Davis Cup tennis player; Scott, the Rhodes Scholar, was his trainer as well as a language expert.

The program was very popular -- indeed, one of my favorites -- except in the

south where some NBC affiliates refused to air the show because it dared to

show an African-American actor on the same level as a white actor. In any event, I have been a Bill Cosby fan for many

years and was pumped to finally have the opportunity to see him live.These "feds" faced their adventures in espionage with skill, humor and some serious questions about their work. Robinson’s cover was as a former Princeton law student and Davis Cup tennis player; Scott, the Rhodes Scholar, was his trainer as well as a language expert.

The show began when he casually sauntered onto the stage in

sweats with a top that said “Hofstra Football” and -- after eyeballing a Duck

football jersey with “Cosby” on the back draped over a chair -- sat down and

started his monologue.

More humorist than jokester, he is a master storyteller who casts parents and kids as natural adversaries.

At

his show, Cosby would relate a story that would spin on tangents so far out to

the edges of the solar system that you wondered if he would ever make it back

to his point. But he nevertheless would, with hilarious effect. His performance

was -- in a word -- wonderfulness.

More humorist than jokester, he is a master storyteller who casts parents and kids as natural adversaries.